I began

writing this review this as I returned to Edinburgh from London. It’s far from

the first time I’ve visited but it was an intense sojourn. I’ve lived in a city

all my life (albeit one that feels more like a village sometimes), but even with

the seemingly endless noise of the Festival crowds still ringing in my ears, my

arrival is met by the roar of the city - a city that is almost too big, too

sprawling, to be appropriately accommodated by the term - and it is keenly felt,

amplified by the briefness of the encounter. Nothing is quiet. Even late in the

night, the city emits a low-level thrum, an electric buzz. Its very scale, in all

directions, presents a kind of loudness, whether sonic or visual, actual or

imagined. Julia Holter’s Loud City Song

does not take London as its titular subject (that honour is bestowed up on

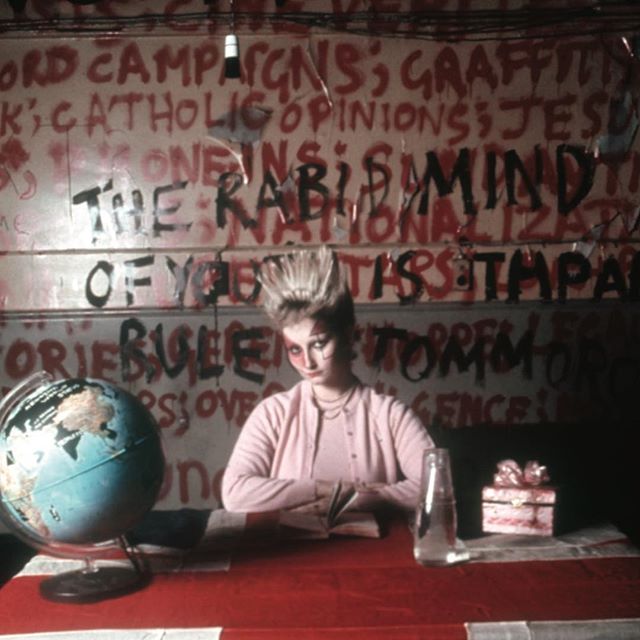

Holter’s native Los Angeles as a transposed setting from Paris for Colette’s Gigi) but it does convey the sense of

wonder, unreality, confusion and fear that a city can reveal as it unfolds

slowly to you for the first time.

Loud City Song opens in an arresting and captivating

fashion with World. “Heaven/All the

heavens of the world.” Her naked voice is slowly dressed by sparse, solemn

instrumentation, strings that creak in heavy groans and sighs in an arrangement

that is reminiscent of Scott Walker and solo Mark Hollis – disjointed lyrics

can only lend further credence to this comparison (a comparison that can easily

be applied to other parts of the record). Holter discusses “All the hats of the

world” and her, her hat and the city’s relationships. Then “Everyday I grow

older/Every day I grow a bit closer to you”. Closer to who? The song closes

thus: “What am I looking for in you?/How can I escape you?” Is it a lover? An

assailant? The listener? The city? Death? World

is a disquieting and enigmatic beginning to an album that asks more questions

than it provides answers to, a quality that makes it all the more enticing -

enthralling, even.

World’s questions linger unanswered with a plunge

into the immediately hypnotic, intense, blissful Maxim’s I. “I don’t understand” Holter declares, and the music

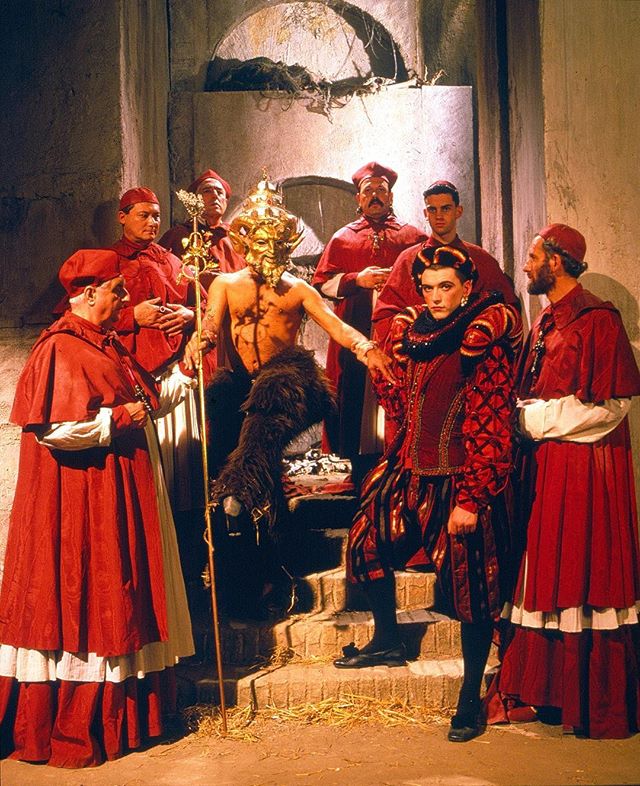

reflects the statement, presenting a scene of cinematic awakening. Impressions

of woozy unearthliness recur throughout, and while this has been Holter’s

stock-and-trade since her debut album Tragedy,

the greater possibilities - and constraints – of recording in a ‘proper’ studio

for the first time have galvanised her sense of the otherworldly in a far more

compelling way. He previous record Ekstasis

was full of ethereal melodies and disembodied lyrics, but it occasionally

drifted dangerously close to the New Age insipidity of Enya. Such a flirtation

occurs only once on Loud City Song,

at its midpoint of (Barbara Lewis cover) Hello

Stranger – it’s just a bit too ambient and uncomplicated for its own good,

letting swathes of digital reverb do most of the work; that it is a cover

speaks volumes of the strength of Holter’s songwriting.

Hello Stranger does provide a necessary break in the album,

for all its mildly irritating execution. The album has a dizzying and at times

overwhelming build. The third track Horns

Surrounding Me pulses insistently then breaks into coruscating organs,

delayed vocals and clouds of billowing horns that threaten to engulf both

Holter and the listener; the following In

The Green Wild builds playfully around lolloping double bass, detuned sound

effects and chatty backing vocals before drifting into another place: “There’s

a humour in the way they walk/Even the flower walks/But doesn’t look for me/It

walks just as it’s grown/It’s laughing so naturally/Ha ha ha ha”. Is this the

disoriented city-dweller in the country (as is suggested by the title), or

could it be the reverse?

After the

wafting ambience of Hello Stranger, Maxim’s II is a curious mix of the

acoustic and the synthesized, and brings to mind early solo Brian Eno, as this

album occasionally does. Something in its mix of light and shade, pop hooks and

out-and-out strangeness, as well as the recurrence of a certain kind of vocal

double tracking that echoes Another Green

World or Taking Tiger Mountain by

Strategy.

Loud City Song continuously throws curveballs – who expects

the almost aggressive Maxim’s II to

be followed by the genuinely beautiful piano-and-strings ballad of He’s Running Through My Eyes? Who could

expect that to be followed by the playful foray into ‘80s-style MOR pop (albeit

a thoroughly subversive and somewhat surreal one, despite the synthetic bossa

beat and oh-so-smooth sax solo), This is

a True Heart? And then, who could expect the unashamedly cinematic (there’s

that word again) finale of City Appearing?

On the latter, Mark Hollis once again springs to mind, as does The Walker

Brothers’ weirdest moment The Electrician,

and this follows a track that sounds a bit like Spandau Ballet or Chris de

Burgh if they were

female-and-interesting-and-really-good-not-totally-atrocious.

City Appearing opens from a bare voice (like World) and into a slow ecstasy, “Taken

by surprise/Taken through the city”. It’s a spaced-out late night taxi drive, a

neon sunrise through a rain-spattered window. A cacophony builds, dazzling,

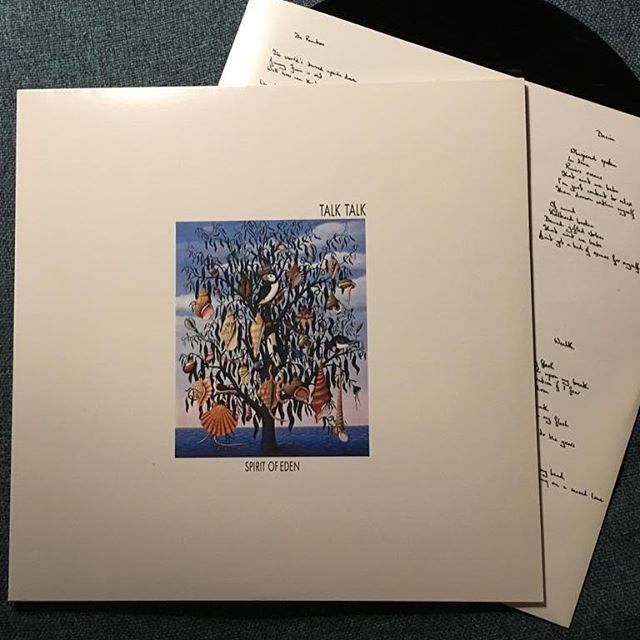

spectral - late period Talk Talk on MDMA - then bursts, shimmers…and it’s gone.

Like a dream you never want to end, the release into the real word is a

shocking one. Dreams tend to slip away over time, become less detailed,

degrade; in this sense Loud City Song

is far less like a dream and more like a city: one' s experience of it is a

continually renewing process of revelation; this record unveils new corners,

light and dark, with every visit – disquieting, elusive and seductive.

'Loud City Song' is available on Domino Records now, on CD, LP and download formats.

Andrew R. Hill